When J.R Simplot Co. announced in May 2002 it would close its potato processing plant in Heyburn, Idaho, and put nearly 650 people out of work, many feared southern Idaho’s Mini-Cassia area (Minidoka and Cassia counties) would dry up like Idaho’s mining ghost towns.

“People were really worried, and it absolutely was a tough time,” economist Jan Roeser said.

But as the 15th anniversary of that day approaches, the local economy seems to be thriving.

Minidoka and Cassia county’s population, which dipped after the plant’s 2003 closure, began a slow ascent in 2007 and now has grown by more than 3,000 people. Since 2009, the area has added 3,344 jobs. Unemployment dropped to a low 3.1 percent last year. And on the same site where Simplot produced french fries, workers now make cheese, provide drug counseling and wash semi trucks.

How did Mini-Cassia accomplish its phoenix rise? In short, the community embraced the costs of growth.

Motivated by Simplot’s departure, Burley, Rupert and Heyburn voters approved bond issues to expand and upgrade wastewater systems. That allowed Brewster Cheese Co., Dot Foods, Fabri-Kal, High Desert Milk, Gossner Foods and other companies to come to Mini-Cassia, stabilizing and diversifying the economy.

Motivated by Simplot’s departure, Burley, Rupert and Heyburn voters approved bond issues to expand and upgrade wastewater systems. That allowed Brewster Cheese Co., Dot Foods, Fabri-Kal, High Desert Milk, Gossner Foods and other companies to come to Mini-Cassia, stabilizing and diversifying the economy.

“The wastewater improvements sent a strong message that we don’t want to sit on our sorrows,” says Roeser, a regional economist with the Idaho Department of Labor. “We want to make changes.”

And the changes worked.

“People were concerned about Simplot closing,” said Mark Mitton, Burley city administrator. “It’s hard for a community to absorb hundreds of lost jobs and put that many people back to work.”

The 650 workers displaced in the Heyburn plant’s phased shutdown were offered severance bonuses for staying until the end and training programs to prepare for new careers. But some workers still struggled to find jobs with similar pay and benefits as they ate up retirement savings or lost their homes and cars.

And the impact rippled through the community.

“It was pretty traumatic,” Roeser said.

The loss of a major employer hurts the tax base, the housing market, the suppliers of goods to the business and—as the newly unemployed have less money to spend—a host of support businesses such as grocers, banks and movie theaters.

Potato growers who contracted with Simplot, John Remsberg said, scrambled to find other stable markets for their potatoes or undergo the process of switching crops. That meant investing in different equipment and selling off potato harvesting equipment.

Remsberg, a Rupert grower who contracted his potato crop with Simplot from 1976 until it closed the Heyburn plant, says potatoes are expensive to grow. When prices are low, farmers “can lose their rear.” And banks that loan the money to grow potatoes prefer that growers have contracts in place, stabilizing the market price.

Coming off a few good years with some money in the bank, Remsberg, now 76, retired from farming after the Heyburn plant closed. At Remsberg’s post-retirement farm sale, the market’s glut of potato harvesting equipment meant he got little more than the price of scrap iron for his.

In 2006, Mini-Cassia took another hit. Kraft closed its Rupert plant, putting another 100 people out of work. The problem was compounded by the recession that hit at the end of the decade.

The unemployed who were able or willing to move likely regained their footing more quickly and were more likely to match their former wages. But it’s common for Idahoans to be reluctant to relocate, Roeser said, making the recapture of wages more difficult.

The late Burley councilman Denny Curtis knew J.R. Simplot, a businessman who grew up in nearby Declo. Curtis and Mitton began discussions with Simplot shortly after the plant’s closure on a deal that would help the community get back on its feet. The deal: one empty processing plant.

“Simplot called it the $22 million gift, and the reason they said that is they were able to write it off on their taxes,” says Mitton.

The deal didn’t come without effort. Mitton and Curtis drove to Boise about 15 times to discuss the deal with Simplot and spoke on the phone with him at least that many times. In March 2004, the company gave the city of Burley the entire 278-acre parcel, which included the potato plant, the company’s wastewater facility across the Snake River, property east of U.S. Highway 30 and property west of the plant. The city incurred $52,500 in costs to take over the property—and Burley’s industrial park was born.

To manage the industrial park, Burley contracted with The Boyer Co., which pays to develop the park and gives the city 10 percent of the gross rental revenues. The city has some costs for lighting and lift stations, but last year the city received more than $118,000 in its share of rents from the property. Simplot continued leasing the freezer from the city until 2013. The structures in the industrial park are nearly all leased, Mitton said, but the park still has room for construction.

Since the Simplot plant’s closure, Mini-Cassia has recruited employers in a variety of sectors.

“I’m not saying Mini-Cassia is totally out of the woods,” says Roeser, because the area now deals with growing pains like housing shortages and wage competition.

But another indicator of a vital community, she said, is the need to build new schools.

After voters passed a bond issue in 2015, Cassia County School District is building schools in Burley, Declo and Raft River and upgrading many others.

“That’s an indicator of a growing work force,” says Roeser.

Fortunately, Roeser said, the Simplot closure came at a time when Magic Valley leaders had also begun to work together at regional economic development. And Mini-Cassia officials doubled efforts to diversify the economy—to lessen the effect of any future business closures.

“Diversity is the key to a healthier community,” says Roeser. “If the baskets are split it’s easier to bear.”

Yes, Burley’s industrial park is in smaller Heyburn, so Heyburn and Minidoka County receive the taxes. (Most of Burley’s city limits sit in Cassia County.)

Mayor Cleo Gallegos, who has lived in Heyburn for more than 50 years and was on the Heyburn City Council when the Simplot plant closed, directly felt the effects of the plant’s shuttering, as her three brothers, mother and father lost their jobs. Being on the council during the closure announcement and its aftermath, she said, was a roller coaster.

Now, Gallegos says giving Burley the plant was the right thing for Simplot to do.

“Looking back, I don’t know if Heyburn would have withstood the impact of having it just sit there,” says Gallegos. And Heyburn may not have had the resources to develop it like Burley did.

In a battle with Simplot over electrical rates, Heyburn had shouldered huge attorney’s fees prior to the plant’s closure. The city eventually settled out of court and, as part of the agreement, sold its electrical utility to a third party.

“My personal feelings are that Burley getting the property was best for the community,” says Gallegos.

Heyburn received land from Simplot that was later developed as the chamber of commerce and the Heyburn Riverside RV Park, arboretum and walking path.

“It was all sagebrush and tumbleweeds,” says Gallegos. The closure announcement 15 years ago was devastating when it happened, she added. “But look at what has happened in the city since then.”

Heyburn hasn’t entirely recovered, though.

“We use to have two grocery stores and now we don’t. We haven’t completely built it back,” says Gallegos.

Across Highway 30 from the former Simplot plant is Tony’s Service, a gas and convenience store—now the only store in Heyburn that carries groceries. It’s owned by Heyburn native Carolyn Gallegos, who worked at Simplot for 20 years, and her husband, Tony, a Simplot employee for 18 years.

“We felt the impact of it closing a little but not a whole lot,” says Carolyn Gallegos.

An old-school attitude had kept the couple relatively debt free, she says, so the dip in customers didn’t break their business. And it wasn’t long before other businesses started opening in the old Simplot complex.

When Gossner built a new Swiss cheese plant at the industrial park in 2005, Mitton says, it put Burley back on the map with site selectors.

“Every time we had an announcement, it hit all the trade magazines,” he says. “You can’t buy that kind of notoriety.”

Mitton says the city council at the time and the councils since all have supported growing the economy. Burley has been careful to offer grant assistance only to companies that paid good wages with benefits, and city officials do site visits at any prospective employers the city thinks could have an unwanted impact on the community. The city has focused on attracting smaller companies, so when a business closes it doesn’t blast a Simplot-sized crater in the economy.

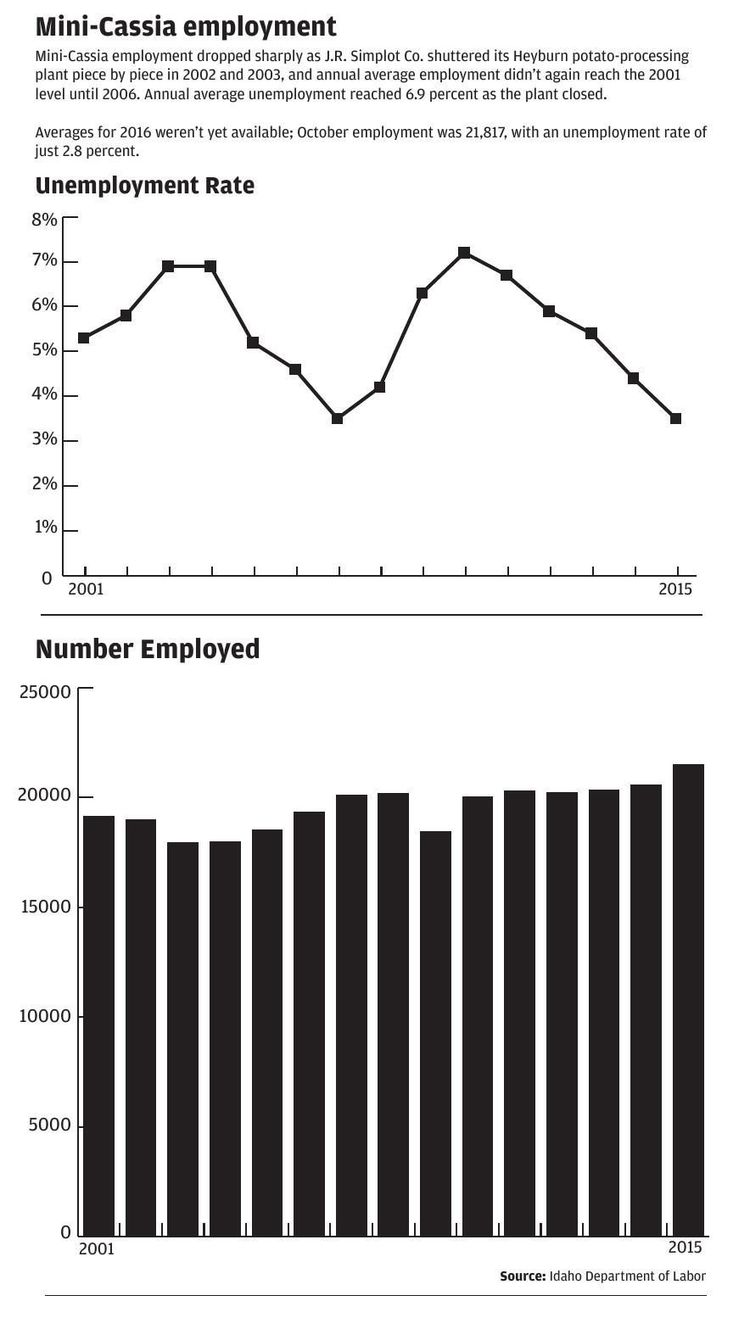

A week ago, the Labor Department’s release of preliminary 2016 data painted a healthy Mini-Cassia economy: annual average unemployment of just 3.1 percent—down from 3.5 percent the year before and almost 4 points lower than the 6.9 percent high reached after the Simplot closure. The two-county region added 300 jobs to bring the number of people employed to 21,782 last year.

Six-hundred and fifty families felt immediate pain and loss when Simplot closed in Heyburn, and countless others lost potato contracts or felt an indirect economic punch. But through taxpayers’ willingness to shoulder the costs of growth, and government leaders’ wisdom to know what needed to be done, the wound healed.

And the resulting diversity made the community more resilient.

Source: MagicValley.com