Story and images courtesy BASF

Kasey Bryant Bamberger is not the first person who comes to mind when most people think of the term “farmer.” In a world of ball caps and faded jeans, she’s more likely to be seen out in the fields wearing a striped sundress with bright purple work boots. Yet Bamberger, the only one of four sisters involved in her family’s third-generation farm, is as passionate as it gets as she tackles the biggest job on earth, helping produce enough food for a rapidly growing world population.

“I grew up around agriculture, but during that time, it wasn’t very common to have women returning to the farm,” says Bamberger, whose farms span six counties in southwest Ohio. “Farming keeps you on your toes. We’re faced with many variables that are out of our control. In my eight years here, we’ve received a different weather pattern every single year.”

The effects of climate change are impacting farmers like Bamberger across the U.S. Extremes such as droughts, floods, and strong winds are becoming more common.

“Every year, we go into the growing season with a plan,” says Bamberger, whose family manages 20,000 acres of corn, soybeans and soft red winter wheat. “But we’re fully aware Mother Nature might have a different one.”

Bamberger says that requires a lot of data-driven decisions and experience: “Our springs have become a lot shorter and harder to manage because of heavy rainfalls,” she says. “The planting window has become narrower, requiring more equipment and more people to do the work in a shorter time frame.”

More than a Farmer

These days, farmers are much more than just farmers. They’re agronomists, meteorologists, soil experts and so much more. They must balance the effects of a changing climate and the demands of a changing world. They’re the original stewards of the land, and their livelihood is inextricably linked to a healthy environment.

“Taking care of the environment, taking care of the soil is hands-down the most important thing to us as an operation and to every American grower,” says Bamberger. “Every grower around the globe will utter the same sentiment, because this is our livelihood.”

The idea of healthy soil is not new in farming, but it’s the driving force behind today’s carbon craze. Scientists and thought leaders believe farmers, particularly those implementing carbon farming practices. are in a unique position to be part of the solution to a warming climate.

At the virtual Leaders’ Climate Summit in April 2021, President Joe Biden emphasized the importance of agriculture in carbon reduction. “I see farmers deploying cutting-edge tools to make the soil of our Heartland the next frontier in carbon innovation,” Biden said. Agriculture is both a victim and contributor to climate change. According to the EPA, agriculture and forestry emit around 10.5% of total U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. On the other hand, it has a role to play in curbing greenhouse gas emissions.

There’s been much discussion about how to create a way for farmers to earn credits for the climate-friendly practices they’ve implemented, or will implement, in their operations.

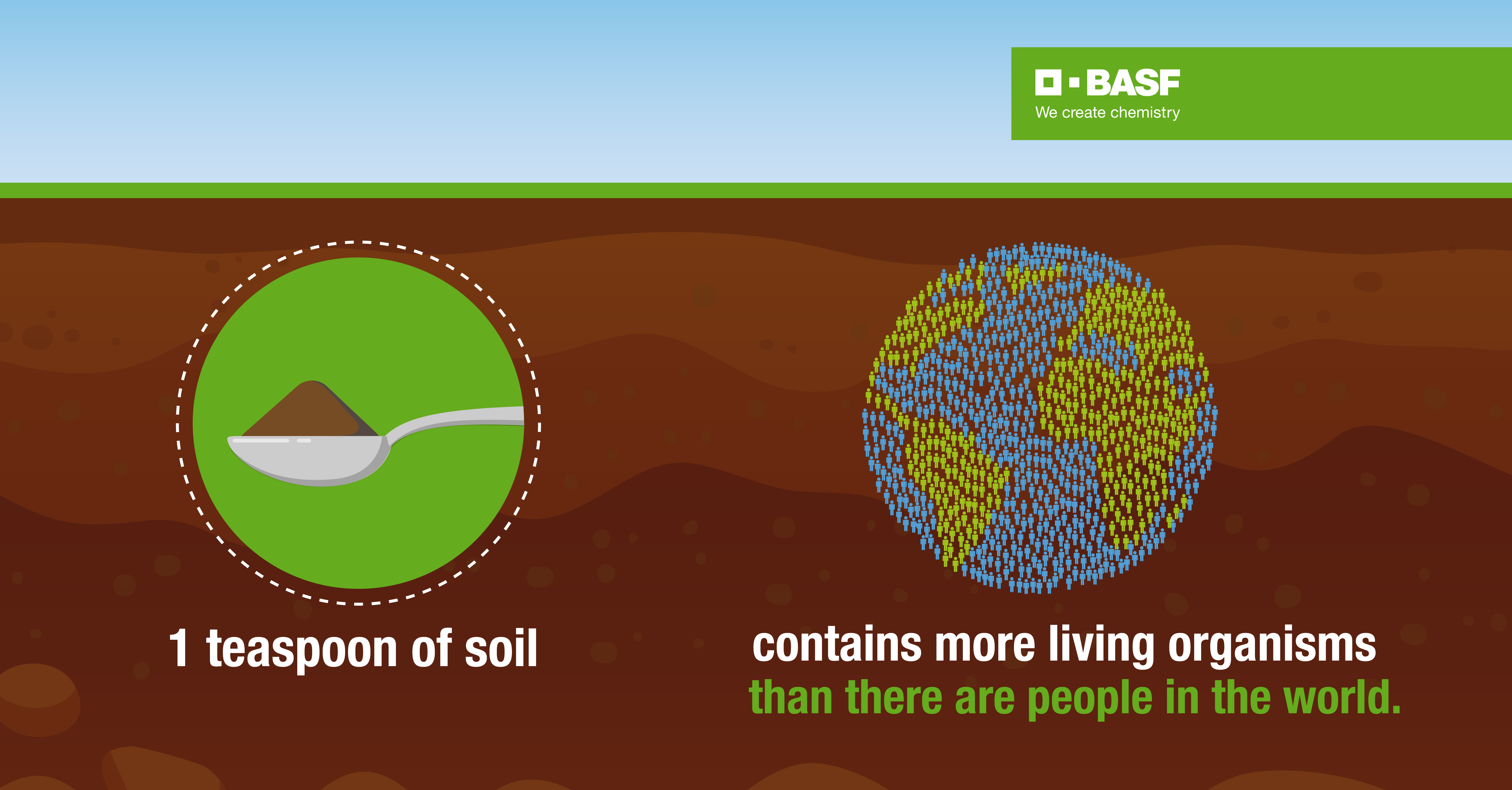

Soils and climate change are intimately linked. There are more soil microorganisms in a teaspoon of healthy soil than there are people on the planet. Behind oceans, soils are the second largest reservoir of greenhouse gases on earth. Soils not only help to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but can also help farming operations be more resilient to increasingly unpredictable weather patterns. Healthy soils make farmland more productive, reduce soil erosion, and improve soil structure, thus improving the quality of ground and surface waters.

What’s Driving the Carbon Craze?

Traditional farming methods that sequester carbon, such as minimal or no plowing of fields (no-till), rotating crops, and planting cover crops, have existed for millennia. So, what’s causing the hype around carbon farming now? The short answer: money.

Carbon stored in soil could soon become its own commodity crop. As large companies look to offset their greenhouse gas emissions by paying for sequestration and removal, the demand for carbon credits is accelerating worldwide. Farmers are not only feeding the world, but also are running businesses and want to capitalize on this potential new revenue stream.

“The carbon industry right now almost seems a little bit like the Wild West,” says Bamberger. “There’s a lot of new information rolling out to growers that looks to agriculture as the solution to reducing our carbon footprint. I believe we can help be the greatest solution, but I’m just worried about the rules and regulations that will be passed. My hope is that they won’t be rolled out too quickly.”

Many of the technologies and practices used to generate carbon credits are only cost-effective when done on a massive scale. According to Bamberger, farmers normally implement new practices in incremental steps.

“We started to introduce no-till practices about three years ago on parts of our farm to learn about cover crops,” she says. “Understanding what cover crop species will work in our area has been a winding road. We’ve done a lot of trials on different cover crop mixes, different species and different parts of the field to try to learn more about the species and how they work on our farm. This helps us to not have a negative effect, so that cover crops do not get quickly out of hand. If so, this could prevent us from planting on time, which is essentially what we are trying to avoid.”

Crop Protection Is a Must

Crop protection technology, such as herbicides, plays an important role in helping farmers implement carbon farming practices. Bryant Agricultural Enterprises has partnered with BASF, which has one of the broadest ranges of herbicides in the industry, in a wide array of crop protection initiatives.

“It’ll be very difficult for us to grow the number of bushels of any crop needed without the use of herbicides,” says Bamberger. “With an increasing population that requires food, fuel and fiber, it will be detrimental if we remove the capability to use herbicides. Even as we transition to no-till farming and plant more cover crops, herbicides play an even more critical role. Digital technology has allowed us to spray weeds in a targeted way and not in entire fields. We’re applying significantly fewer inputs today than just six years ago.”

If implemented on a larger scale in the U.S., agricultural soils could draw down more 250 million metric tons of atmospheric CO2 annually, according to The National Academy of Sciences. This will require universal standards for measuring, reporting and verifying agricultural carbon credits and incentives. For now, several companies are banking on carbon with carbon payment programs.

Bamberger is just one of many next-generation farmers continuing the legacy of land stewardship.

“We continue to challenge ourselves to produce crops in a safe and sustainable manner, while making sure our decisions are operationally profitable and environmentally friendly,” she says. “We know as the world population increases, it’s more important than ever to continue to take care of our soils and environment while producing high-yielding crops.”

Agriculture has a big role to play in reducing carbon emissions, but it will take multiple industries coming together to make carbon farming a reality on a larger scale. One thing’s certain: The young farmer wearing a striped sundress with bright purple boots will continue to do her part when it comes to climate-smart farming.