"When there's a drought, everyone gets really into water," she said. "And when it's wet, we don't think about it. But the thing is, we have to be thinking about it all the time."

Groundwater and surface water in the Central Sands have a notably close relationship because of the shallow groundwater table, located about 10 to 15 feet below the surface in most areas.

When you see a lake or a stream, you’re seeing the water table, Nocco said. If water levels go down even a little bit, it can affect lake and stream flow.

And as temperatures rise and longer stretches of intense heat become more frequent, farmers will likely need to rely on irrigation more, Kucharik said. Potatoes can’t be water stressed for more than 24 hours.

For Diercks, it can feel like you lose either way. If it rains too much, the crop suffers and risk for groundwater contamination intensifies. If it doesn’t rain enough, pumping water for irrigation can affect surface water.

"It’s just a matter of how you want to lose sometimes," Diercks said.

An Unpredictable Growing Season

Mother Nature's been difficult the last couple of years, Diercks said, thinking about the sporadic freeze and thaw cycles, intense rains and cooler than usual summer temperatures.

"If those are climate change impacts, then yeah, we're seeing some changes," he said.

2018 went down as the worst crop in the history of Wisconsin potatoes, said Tamas Houlihan, executive director of the Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association.

September rains delayed harvest and before farmers could get into the fields, a devastating early frost in mid-October left some farmers with no choice but to abandon thousands of acres of potatoes in the ground.

"Over 5,000 acres of potatoes were subject to frost and basically useless," Houlihan said. "It was a real disaster."

Potato production contributes about $350 million to Wisconsin’s economy each year. In 2018, roughly 69,000 acres of potatoes were planted across the state.

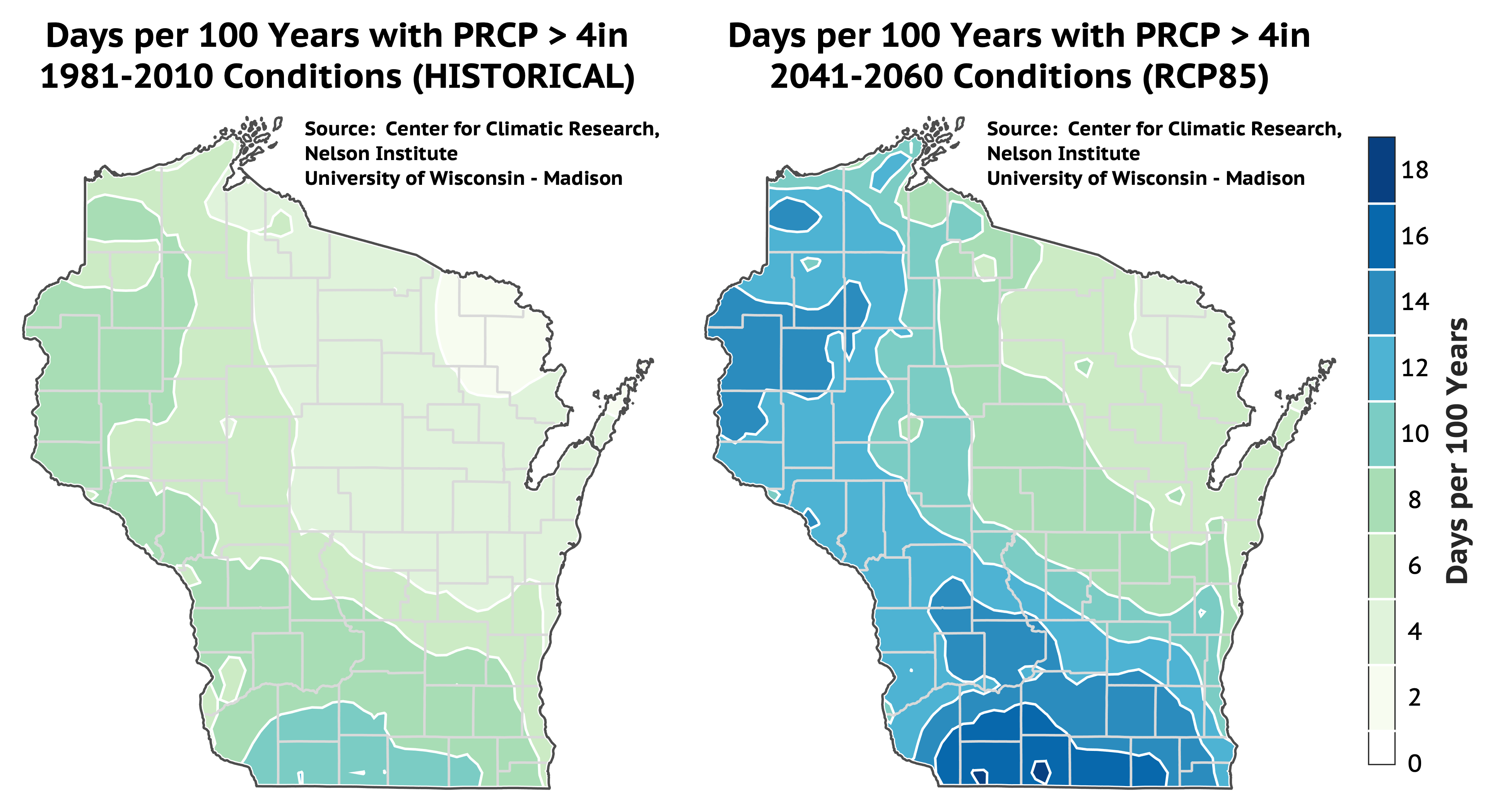

Graph courtesy of Dan Vimont, director of the Center for Climatic Research

While experts are cautious to contribute one extreme weather event — or several challenging years — to climate change, the increasing occurrence points to a warming planet. And there’s no historical record to compare it to.

"The saying is, stationarity is dead," Kucharik said. "That's meaning the historical analogs ... are kind of becoming useless because the amount of variability that we're seeing now, there's nothing there in the past."

Warming temperatures are leading to a longer growing season — which in some ways is a good thing for potato production, but it also isn’t straightforward.

When, and how much precipitation falls, what pests can overwinter here and how well cool weather crops will handle rising temperatures are just some of the questions stemming from the 2 to 8 degree change Wisconsin is expected to see by 2050.

Future of the Crop

Gains in agriculture productivity can in large part be traced to the introduction of nitrogen fertilizers following World War II. Today, while nitrogen use has largely leveled out, it still remains near an all-time high.

Alongside those trends have been advances in genetics and breeding, Kucharik said.

Both Kucharik and Houlihan said potatoes that are bred to be more nitrogen and water efficient will likely be used in the future.

But getting consumers and suppliers to accept genetically modified crops is a challenge, Houlihan said. He argues that to produce the quality and yields the market demands, potatoes that need less water and nitrogen and can withstand variable weather, are going to be necessary in the future.

While there’s widespread consensus among scientists that genetically modified plants are safe to eat, they’re controversial, in part because of a lack of long-term research and criticisms that they increase the use of chemical herbicides.

"With words like Frankenfood ... people are afraid," Houlihan said. "But I do think over time we are going to find out that GMO foods for the most part are safe and they're really necessary."

Diercks is blunt that what customers want often doesn’t align with varieties that are easier on the environment and suited for Wisconsin’s climate.

"What we typically end up with here is the Russet burbank, which is what they grow everywhere for French fries," he said. "But it's a 50- or 60-year-old variety that's not particularly well-suited to our humid climate with warm nights."

"There are things that work better here, but they're a little harder to process," he continued.

If companies want their supply chain to be more sustainable, they need to meet growers half-way, Diercks said.

"If we have varieties that can be more environmentally sustainable, then we need those to be accepted and moved up the food chain," he said. "You can't just continue to ask us to grow and use the same old varieties and just use less water and less nitrogen to grow them — you're going to go out of business doing that."