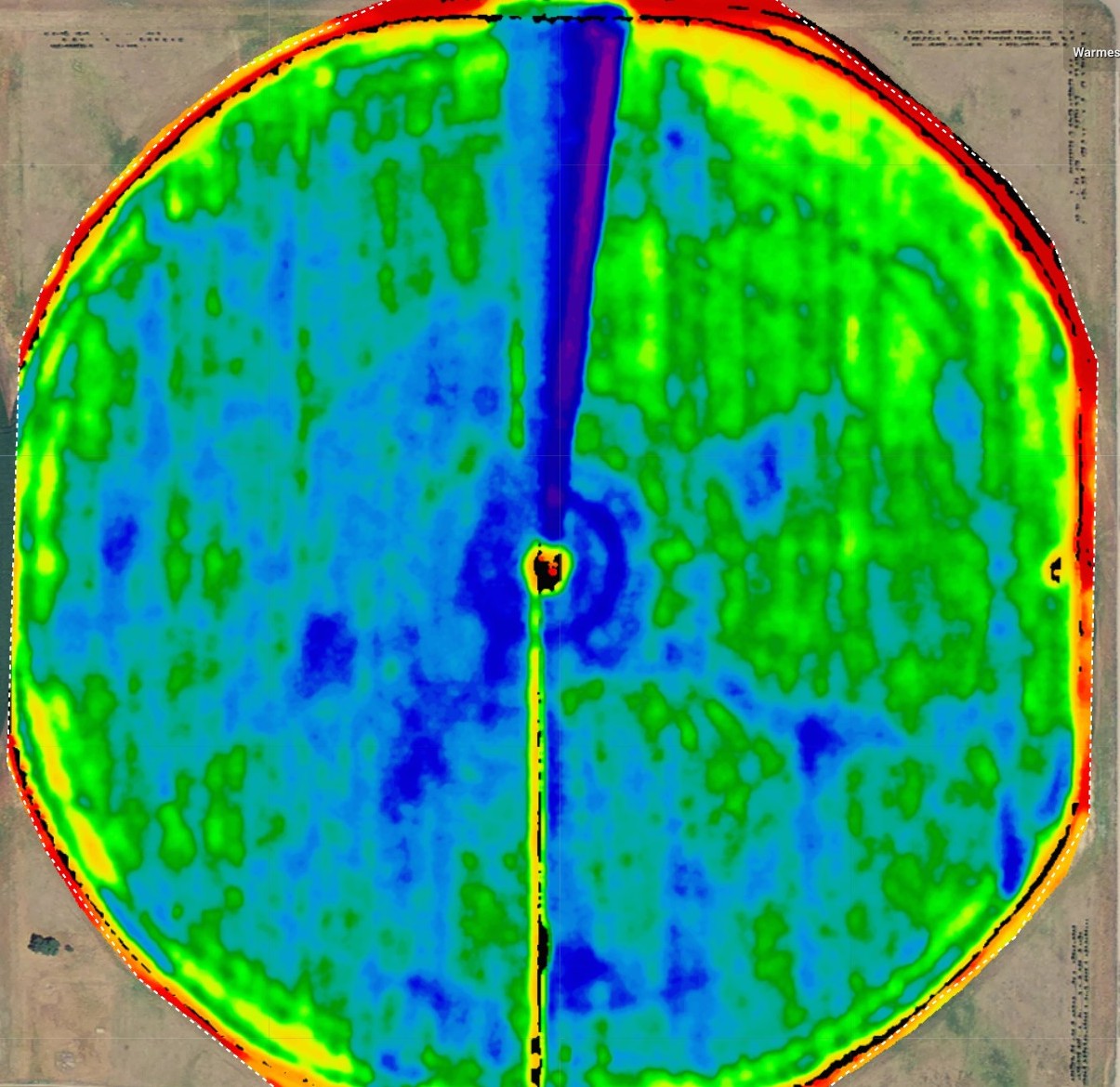

On the screen it’s easy to miss: a trace of purple across a lighter orange disc.

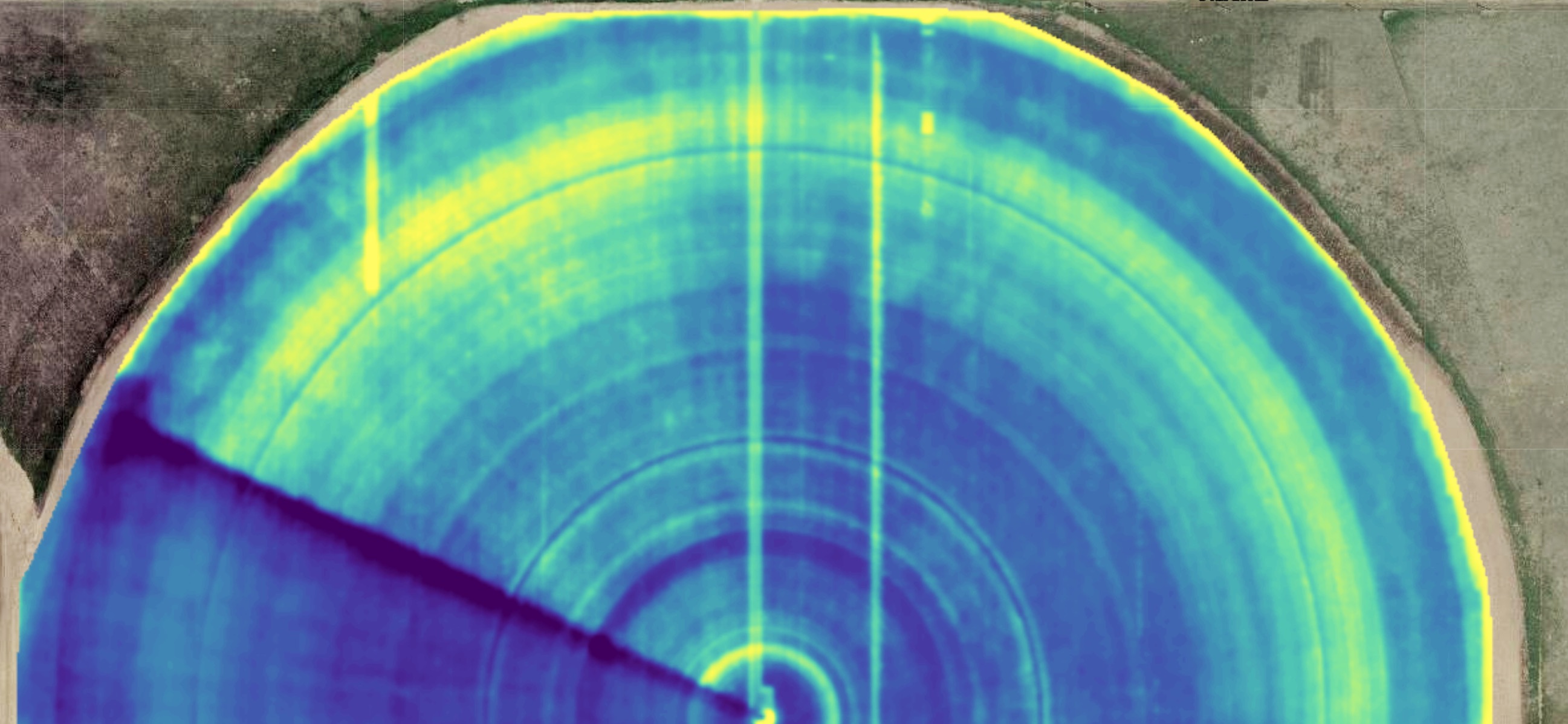

But to Kirk Stueve, a fourth-generation farmer and remote sensing scientist at Ceres Imaging, the ring of color looks like a potential $5,000 loss. That’s because the image—an aerial view of a field of potatoes captured by a scientific-grade thermal camera—reveals a problem with the center pivot irrigation system that over the course of the season could affect more than 30 acres of tubers.

“The purple section is cooler than the surrounding area because it’s being over-watered,” Stueve explains. “It suggests to us that a valve is stuck open, or potentially something more significant.”

“The purple section is cooler than the surrounding area because it’s being over-watered,” Stueve explains. “It suggests to us that a valve is stuck open, or potentially something more significant.”

It’s a straightforward fix once the problem is identified, but the temperature difference that tipped off Stueve to the irrigation problem is imperceptible to a grower on the ground. Moisture probes, satellite imagery, drones—none is likely to reveal an irrigation issue until after it has already impacted the crop.

No Room for Error

No Room for Error

For growers and their partners focused on efficiency, that’s too late for the bottom line.

Will Llewellyn, Ceres Imaging’s advisor to potato growers in the Northwest, describes the challenge growers face every year. As the crop grows less thirsty late in the season, growers must reduce water application in perfect sync with the falloff in demand. If irrigation adjustments lag, the likelihood of experiencing rot or disease in the field increases significantly.

University of Idaho Extension research has found that “over-irrigating by 20 to 30 percent during the growing season can reduce potato yield, quality and fertilizer use efficiency,” lowering returns by more than $150 an acre.

Even isolated incidents of over-watering carry significant risk. Consider the stuck valve spotted by the remote sensing scientist in Ceres Imaging’s thermal capture. Even if the oversaturated soil causes rot in only a small portion of the harvest, that rot spread to unaffected potatoes in storage could result in a total loss of everything in the bin. The lucky grower who acts early enough to prevent this scenario is potentially saving six figures—or even the business.

Even isolated incidents of over-watering carry significant risk. Consider the stuck valve spotted by the remote sensing scientist in Ceres Imaging’s thermal capture. Even if the oversaturated soil causes rot in only a small portion of the harvest, that rot spread to unaffected potatoes in storage could result in a total loss of everything in the bin. The lucky grower who acts early enough to prevent this scenario is potentially saving six figures—or even the business.

Right Solution, Right Time

But Llewellyn believes that in the current market there’s no reason anyone should leave the quality of the harvest to chance. With no shortage of ways for the season to go wrong, Ceres Imaging is developing powerful new tools to help growers get irrigation exactly right.

The company flies fixed-wing aircraft equipped with cameras that capture images across the visible and invisible spectrum. Analyzed in detail by Ceres’s team of data scientists and agronomists using university-validated crop models, the enhanced view of the field provides insights that allow growers to optimize fertigation programs, manage pest and disease outbreaks, and detect irrigation issues before they impact yield or quality.

For large-scale operators, though, reviewing these analyses for hundreds of fields can be time-consuming and unwieldy. That’s why Ceres Imaging is now arming growers with new analytics tools—developed with machine learning techniques and data gathered from years of flights—that automatically sort through and categorize results.

The result? Rather than a pile of uninterpreted imagery or long reports, growers get immediate suggestions on where to follow up first, and why—making management decisions simultaneously faster and more informed.

“Any experienced grower can think of any number of ways they might try to optimize irrigation,” Llewellyn says. “What we want to do with our analyses is help prioritize those interventions most likely to pay off in a big way.”

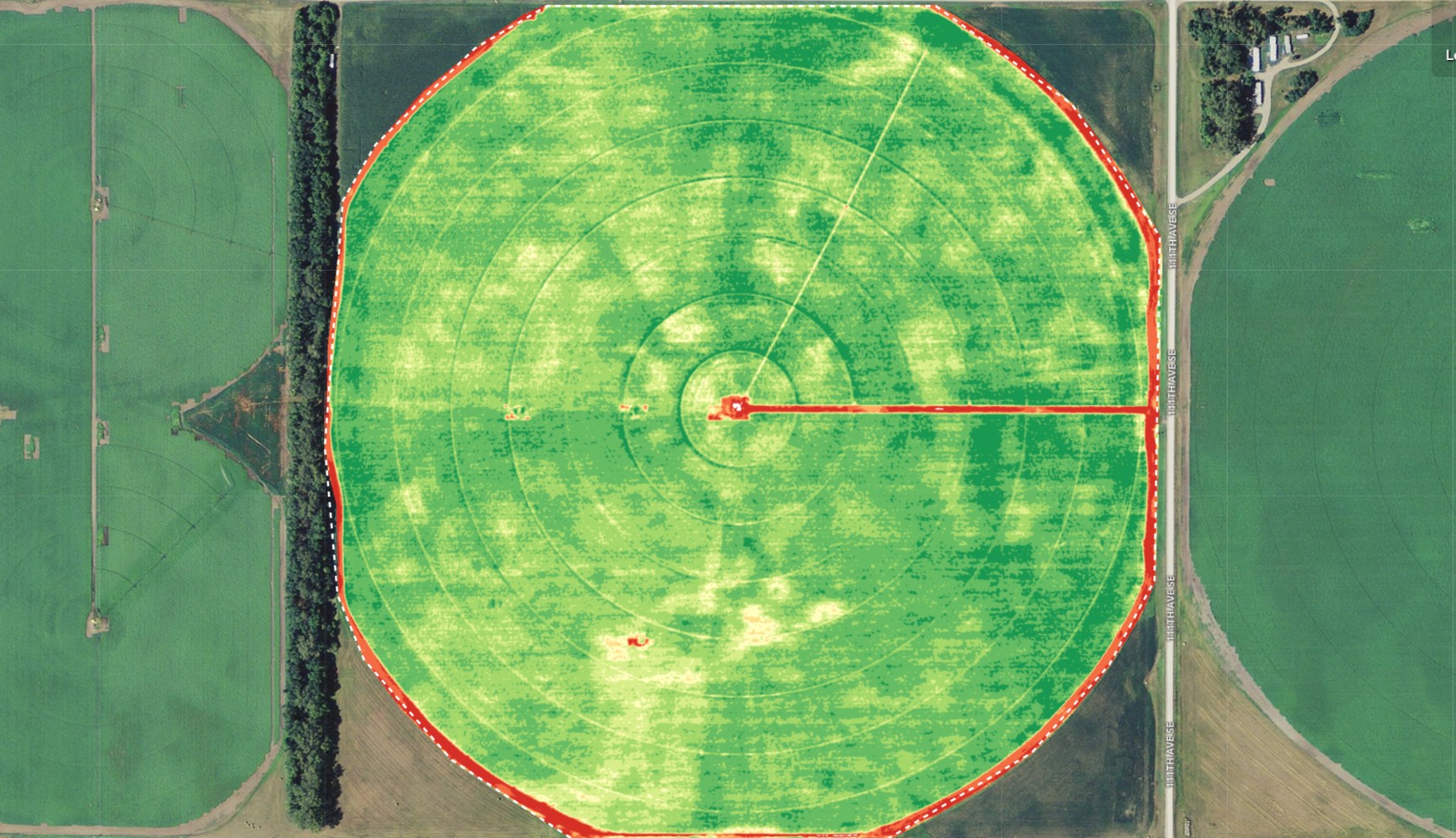

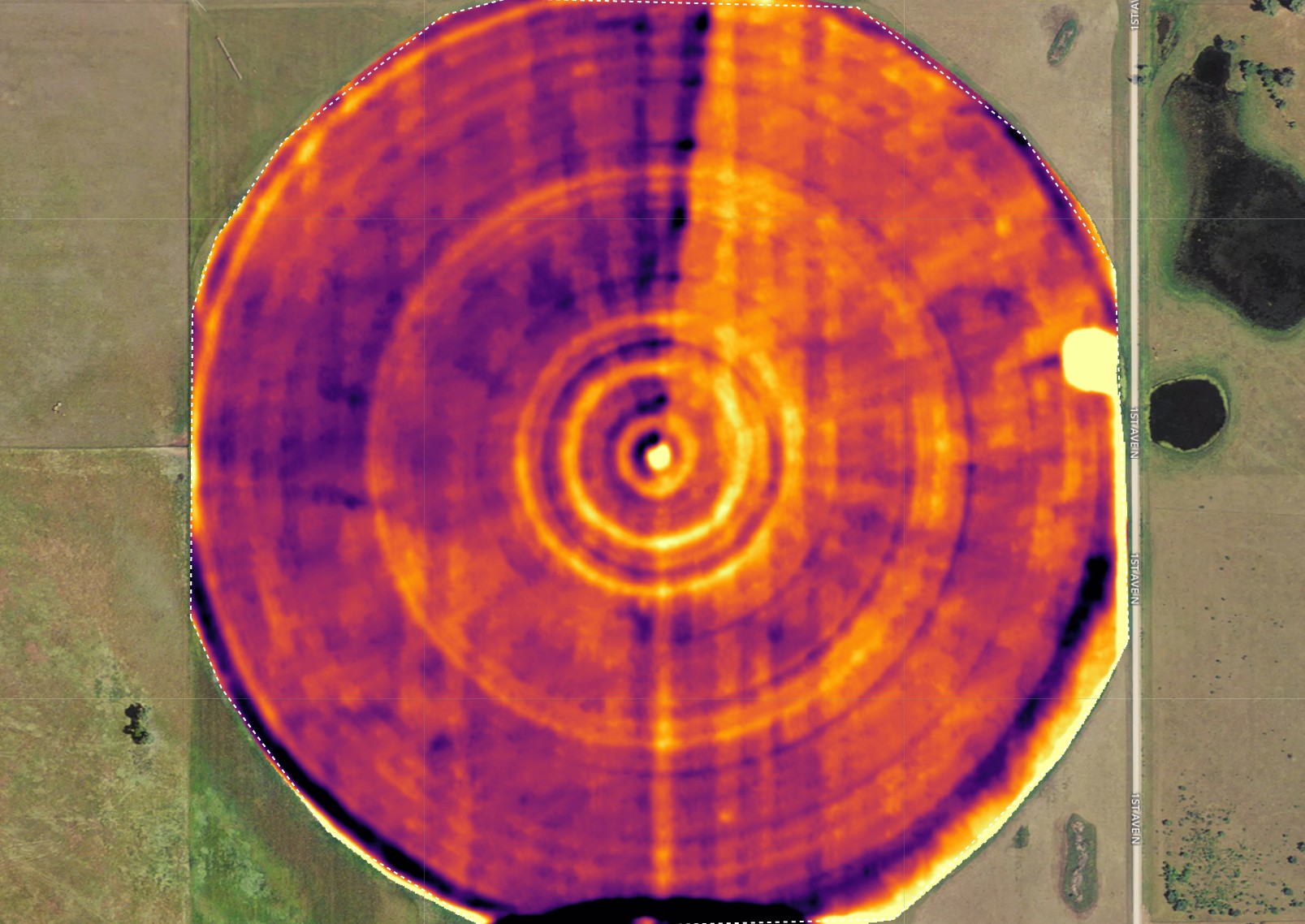

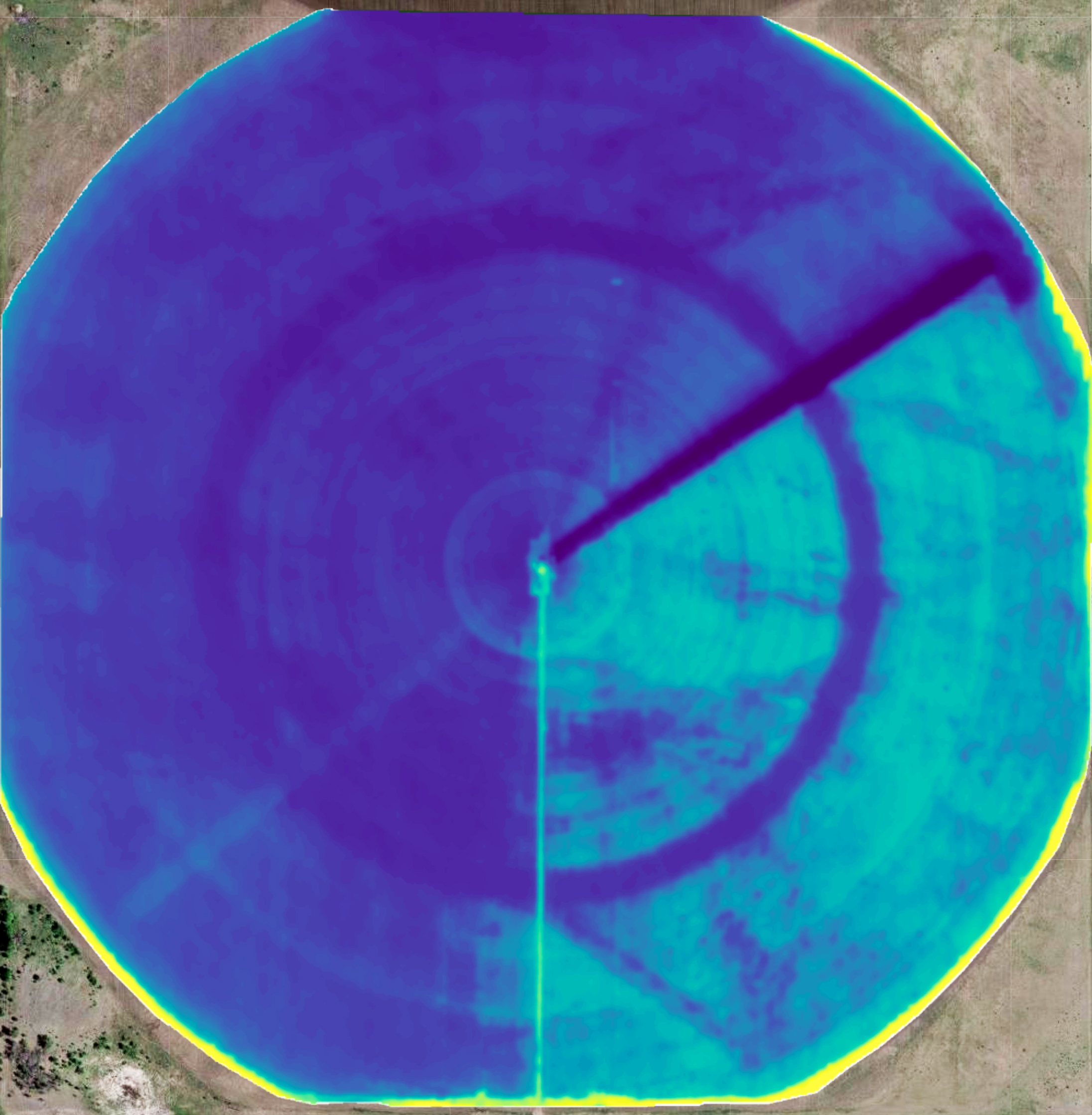

Ceres Imaging flew over pivot-irrigated potatoes in central North Dakota, providing early-season thermal imagery that identified sprinkler problems before potato crops were damaged by over- or under-watering.

The first image shows a dark ring where nozzles that were 13 percent too large caused over-application of water.

In the second image, a lighter-colored ring pattern shows drop pipes that were partially plugged, resulting in under-watering across a band of ground approximately 300 feet wide. A light-colored ring in the center of the image reveals a sprinkler nozzle that was completely plugged. A slightly larger dark ring is from over-watering nozzles.

“If you have any kind of water stress in potatoes, it can lead to fry color problems in french fries,” says agronomist John Vaadeland. “Ceres Imagery helped us to detect irrigation issues we couldn’t visually see early in the season.”